Exploring Art and Identity in Mexico City

Come with me to explore the art of CMDX and the inspiration and history behind this vibrant city

If you know me (which most of my subscribers do), then you know I love art and I travel a lot for work. What you may not know is whenever I visit a new city or country I prioritize going to an art museum. Shopping, take it or leave it, food necessary but circumstantial, I’m going to the museum followed by writing postcards in the park. But now that I have a Substack, my latest work trip to Mexico City inspired me to write about the artist I saw and dig into the history of Art in Mexico.

I was really moved by the modern art museum, Museo de Arte Moderno, and visited the Museo Nacional de Anthropology, which featured historical art, relics, and artifacts from Mexico’s ancient civilizations. The Anthropology Museum had the most unique patterns, imagery, gods, so unique to anything I’d ever seen before. Whereas at the Modern Art Museum I saw familiar artistic techniques, periods, and even direct inspiration for today’s fashion.

It got me thinking a lot about originality and notoriety. Do we as humanity continuously reinterpret the same artistic principles and inspiration, color, composition, subject, perspective of the past? Is there anything that is truly original or is it all based off the works of the previous generations. And In terms of notoriety, how do we as humanity determine the artist we remember? Are the most influential and prolific artists really those we celebrate in the biggest museums today?

We’ll discuss these questions and dive into some history about Mexican art!

Surrealism and The Mexican Landscape:

Let’s kickoff with Surrealism. Some of the most iconic surrealism imagery depict features of Mexican landscape. Upon further reading, Dali himself after visiting Mexico said, “There is no way I’m going back to Mexico. I can’t stand to be in a country that is more surrealist than my paintings” Mexico became a haven to European Surrealist artists and free thinkers during World War II with several artists building community in Mexico and produced art inspired by the mixture of magic (mythology/folklore/celebration of death) with the sharp rise in industrial development after the revolution.

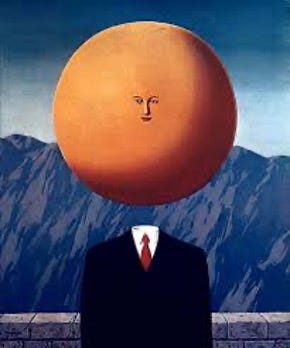

The Surrealist influence was on display at the main galleries of the Museo de Arte Moderno. Surrealism is characterized by dreamlike scenes that depict the irrational, subconscious, most closely tied with revolutionary and anti-establishment ideology. The most well-known, artist of this period include Salvador Dali, René Magritte, Max Ernst, and Joan Miró (all European). This painting by Nahum Zenil (left) reminded me so starkly of Rene Magritte. However, Zenil’s piece was completed in 1998 in Mexico, while Margette was in his prime in 1940s.

This chair by Mexican artist, Pedro Friedberg, reminded me of Daniel Rosebery for Schiaparelli. Schiaparelli has been the top fashion house of 2024/2025 drawing heavily on surrealist imagery like their lobster dress, gold toed shoes, which are all inspired by the original owner, Elsa Schiaparelli, who was heavily influenced by the Surrealist movement and even had a close personal friendship and collaboration with Salvador Dali.

While other pieces feel unique to the Mexican landscape and identity such as Carlos Orozco Romero’s “La Manda” or in English “The Vow.” Which combines surrealist principles but was inspired by a photo of Mexican worshipers self-inflicted pain during a worship at the shrine in Jalisco. This imagery speaks to the layered history of Mexico, where devotion is often intertwined with sacrifice, penitence, and physical suffering. Romero’s work captures this fusion, blending surrealism’s psychological commentary with Mexico’s enduring relationship to faith and bodily expression. Similarly, Emilio Ortiz’s La Ceremonia offers a surrealist view of everyday life. The painting presents a Mexican table setting with—objects rendered in a hyper-realistic style yet arranged in a way that defies logic and expectation. The piece feels both familiar and strange, evoking an homage to Mexican home life but something also destabilizing…

Frida Kahlo, one of Mexico’s most iconic artists, leaned deeply into the country’s mysticism and mythic identity. However, she did not officially associate with the Surrealist movement, largely because of her commitment to creating a uniquely Mexican artistic identity—a vision she shared with her husband, Diego Rivera. Rivera, the most prolific of the Mexican muralists, focused on capturing the spirit of the post-revolutionary era through large-scale public art. (More on him in the next section.)

Both Kahlo and Rivera were deeply invested in building a distinctly Mexican style, identity, and artistic community. This often created a sense of tension with European expats who had fled the war. Yet, despite that friction, the influence of Surrealism within and alongside Mexican art is undeniable—its dreamlike imagery, symbolic language, and psychological resonated with Mexico’s rich cultural landscape and post-revolutionary society.

I’d also like to shout out, Futurism paintings like the one below, that mirror the surrealist characteristics of juxtaposition with commentary on mass industrialization and its impact on community, culture, and life.

Development of a Mexican Identity, Diego Reivera

When you walk around Mexico City, you’re bound to encounter breathtaking murals—many of them created by or inspired by Diego Rivera. In 1921, Rivera was commissioned by Mexico’s post-revolutionary government to create a series of public frescoes aimed at unifying the nation through art. His murals celebrated Mexican society, culture, and values in the wake of the 1910 Revolution.

Rivera’s style was shaped during his time studying in Europe, particularly in France and Italy, where he was influenced by the Cubism of Picasso, the post-impressionism of Paul Cézanne, and the grandeur of Italian frescoes. But after returning to Mexico in 1920 on bequest of the new colonial government, Rivera developed a unique artistic voice. He began drawing inspiration from the everyday lives of Mexican people, as well as from indigenous Aztec and Mayan cultures, blending these historical elements with the modern political themes of his time. The result was a powerful and accessible form of public art that still resonates throughout the country today.

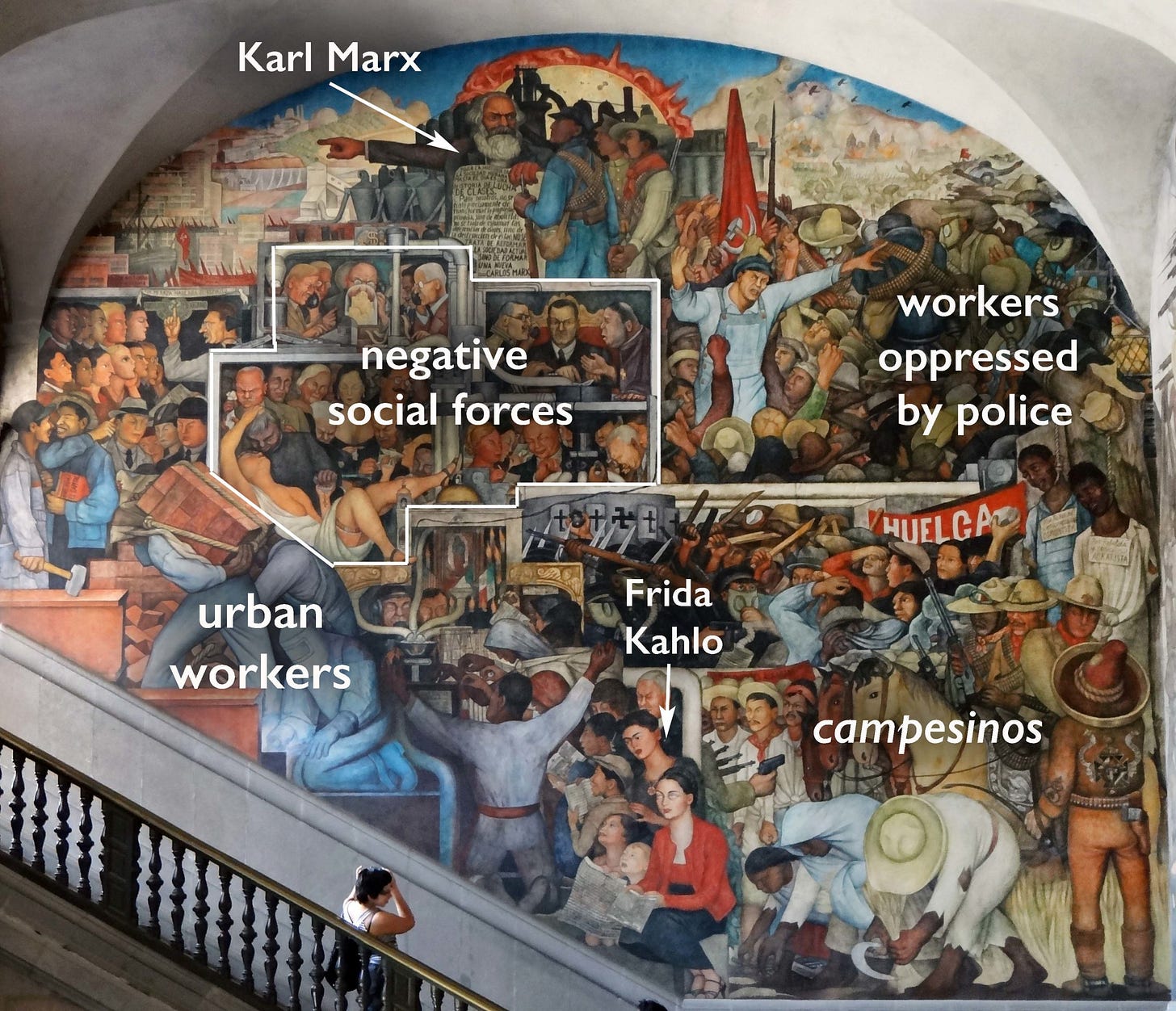

Rivera’s murals aren’t just beautiful—they’re bold, political, and impossible to ignore. You see them all over Mexico City, not tucked away in galleries but front and center in public spaces. One of the most striking examples is his mural series in the National Palace—The History of Mexico. It’s this massive, floor-to-ceiling narrative that wraps around the walls, telling the story of Mexico from ancient civilizations through colonization, independence, and revolution. You see Aztec warriors, Spanish conquistadors, rebel fighters, and scenes of modern industrial life—all packed into a European inspired Fresco.

Rivera’s strong ties to communism show up throughout his work. For example, his exiled friend Leon Trotsky, an ally of Lenin and leader in the Russian Revolution, is depicted in several of his paintings. His murals connect Mexico’s past with the social commentary of the past, violence of the revolution, and dreams for the future.

Originality and Noterietay

So, to close, with where we started. Originality, before this research, I was in the camp that originality was impossible. All ideas have been created and anything new is just iterations of previous works. But this study taught me that inspiration doesn’t equate to duplication. Just because Rivera studied cubism, and Picasso doesn’t mean his creations are derivative. He built a unique style inspired by his country, for his people. He combined the ideas of Fresco, Communism, with his lived experience to build something new.

But what I think is difficult is when notoriety comes into play. There’s a reason when we think about art, most people think of a few artist and signature paintings. Picasso, Monet, Da Vinci! The most famous paintings get plastered into the modern memory and define whole movements but can erase the genius that inspired them. Particularly, if those who inspired them or were inspired by came from marginalized communities. The history of art is riddled with contributions that have been overshadowed by the fame of more prevalent voices elevated by wealth and power.

So, I guess my point is celebrate art in all its forms! Go to the museums off the beaten track, be inspired by the history they depict. Follow your interests and curiosity, whether it’s food, shopping, science, history and dig into the layers of innovation that inspired what you see today! Okay… getting off my soap box!

I’ll leave you with a few of my fav pics from my trip :)